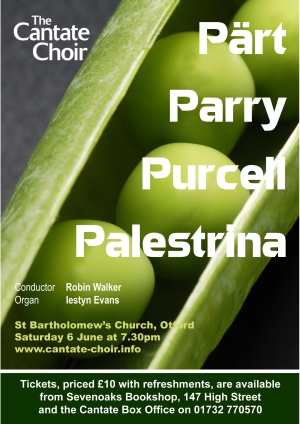

7.30pm, Saturday 6 June 2009 – St Bartholomew’s Church, Otford

Soloist

Iestyn Evans – organ

Programme

H. Purcell 1659–95 My Heart is inditing

H. Purcell Voluntary in G major

G.P. Palestrina 1525–94 Exsultate Deo

G.P. Palestrina Ricercar del quinto tuono

G.P. Palestrina Tu es Petrus

A. Pärt b. 1935 Pari Intervallo

A. Pärt The Beatitudes

C.H.H. Parry 1848–1918 Songs of Farewell

C.H.H. Parry Chorale Prelude on “Croft’s 136th”

Programme notes

The complex and many-faceted only confuses me, and I must search for unity. What is it, this one thing, and how do I find my way to it? Traces of this perfect thing appear in many guises – and everything that is unimportant falls away.

Arvo Pärt wrote this in the mature years of his life after a lengthy period of self-imposed silence as a composer. His new style, the style we largely know in his popular choral works, developed at this time and is unrecognisable from his early works. All traces of discord and complexity are gone. He is fixated on the triad (doh-me-soh) and its variations. He moves the vocal parts subtly through the inversions of simple chords, which technique he referred to as tintinnabulation, the sound of bells.

It is thought that Edgar Allen Poe was the first to use ‘tintinnabulation’ to describe the sound of bells, specifically the tinkling and jingling of bells, in his poem ‘The Bells’, which was famously set in a Russian translation by Rachmaninov. Pärt goes on to say, ‘I work with very few elements — with one voice, two voices. I build with primitive materials —with the triad, with one specific tonality. The three notes of a triad are like bells and that is why I call it tintinnabulation.’

So how does this sit with the rest of our programme? What are the common threads? Well, to be sure, our four composers all have family names beginning with P! All were mature and accomplished choral composers when they wrote the pieces we perform tonight and as such we are hearing arguably their best and most defining work. All held positions of distinction and influence in their musical worlds of the time. Palestrina was Maestro di Capella in Rome’s great churches St. John Lateran (1555-60) and St. Maria Maggiore (1561-6), writing for the Pope and cardinals. Purcell was organist at the Chapel Royal from 1682 and wrote music for many royal occasions, including ‘My Heart is Inditing’ for the coronation of James II. Hubert Parry joined the staff of the newly opened Royal College of Music in London and was its Director from 1894 until his death. He also succeeded Stainer as Professor of Music at Oxford University in 1900. Arvo Pärt was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1996 and named International Composer of the Year in 2000 by the Royal Academy of Music in London.

Charles Hubert Hastings Parry had an interest, some say Darwinian, in the evolution of the arts and of music in particular. He wrote books and essays on the subject charting the progress from the simplest utterances to the supreme achievements of composers and musicians. “The story of music has been that of a slow building up and extension of artistic means of formulating in terms of design utterances and counterparts of utterances which in their raw state are direct expressions of feelings and sensibility.” He argued that the vocalising of feelings is something common to all sentient beings, for example a dog greeting a master, the chorus of hounds when spying the fox, a cow wailing for her lost calf or the exuberant baby with gurglings and percussive rattle.

This takes us right back to Palestrina’s Exsultate Deo, composed in 1584 on the words of Psalm 81:

Sing aloud to God our strength;

Make a joyful shout to the God of Jacob.

Raise a song and strike the timbrel,

The pleasant harp with the lute.

Blow the trumpet at the time of the New Moon,

At the full moon, on our solemn feast day.

For this is a statute for Israel,

A law of the God of Jacob.

In no other art form than choral music, whether sacred or secular, is it possible to express so directly sentiments and feelings: joy, sorrow, praise, despair, longing, satisfaction, this world and the next. And in expressing ourselves so directly, we can move others who listen to the same sensations be it reverence, cheerfulness, praise or prayer. “Get out there and bang something!” the psalmist is saying.

All four composers had a reverence for the music and traditions which had gone before them, in particular for the forms of madrigals and motets. These are short pieces for multiple voices which build layers of tone, harmony, texture and melodic interplay from often simple motifs designed to capture some element of the meaning of the text. The Pope was tickled pink by Palestrina’s upsurging ending to ‘Tu es Petrus’ (I shall make you the guard and keeper of the gate of Heaven.) Pärt’s ‘Beatitudes’ (Blessed are the poor in spirit etc.) get steadily higher and stronger until the final resounding Amen. Purcell chose some curious words for his coronation anthem but my goodness he sets them with gusto. It is full of bouncing dotted rhythms and syncopations that make you want to laugh out loud with the sheer joy of it all.

However, Parry’s ‘Songs of Farewell’ form the most substantial contribution to this panoply of giants. Written separately over a period of some nine years, he died before hearing them performed as a complete set. He long admired the English Poets from the Elizabethans to his late Victorians. Here he chose Henry Vaughan (1622-1695), John Davies (1569-1626), Thomas Campion (1567-1620), John Gibson Lockhart (1794-1854), and John Donne (1572-1631). Parry was a rationalist and agnostic but valued biblical texts and spiritual writings as a part of his cultural heritage of which he felt very proud. These poems are not overtly religious but provide mystical hints of the transitoriness of life on earth and the possibilities of life beyond. These settings steadily build in complexity in a Darwinian trail of evolution from simple chordal SATB settings, adding one more vocal line with each motet until the mighty double choir setting of ‘Lord, let me know mine end’, which sets Psalm 39, the only biblical text in the set.

‘Traces of this perfect thing’ are present in all these works and during this concert, we trust that ‘everything which is unimportant falls away’.

Sara Kemsley