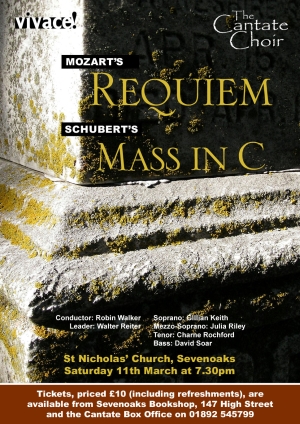

7.30pm, Saturday 11 March 2006 – St Nicholas’ Church, Sevenoaks

Soloists

Gillian Keith – soprano

Julia Riley – mezzo-soprano

Charne Rochford – tenor

David Soar – bass

Hazel Brooks – leader

Programme

Mozart – Requiem

Schubert – Mass in C

Programme notes

The pairing of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Requiem with Franz Schubert’s fourth Mass ought to be a marriage of great works by two great composers. Scholars have argued, and continue to do so, over whether Mozart’s final work was born great or had greatness thrust upon it by the romantic and mysterious circumstances surrounding its genesis. Schubert, by his own admission, knew that his choral works lacked the masterstrokes of his illustrious forbears and decided to have lessons in counterpoint very late in life. What is not in doubt is that both works have rightly held a firm place in the hearts of performers and audiences for around 200 years.

The two composers had much in common. Both were violinists and pianists of prodigious talent. Both were dominated by their fathers. Both remained poor for much of their lives, struggling for positions which would provide money and status. Both died in their early thirties of illnesses which still arouse some debate. Both left behind an enormous body of work, as if they knew that time was short. Coincidentally, Antonio Salieri was Schubert’s teacher and Mozart’s archrival, holding as he did the coveted position of court composer to Emperor Josef in Vienna.

More importantly, both inhabited a musical paradise, although they might not have thought so at the time. Anton Schindler, writing in 1840, described turn-of-the-century Vienna: ‘There was a preference for music without ostentation – music which, whether performed by four voices or four hundred, would work magic on the listener, cultivating his mind and senses, ennobling his emotions… and yet this was not a time of philosophical sophistication; it was rather a period of uninhibited enjoyment, whose purity lasted well into the first decade of our century.’

Schubert’s Mass in C, D452, was written in 1816. It has a very light orchestration with no violas and optional clarinets and trumpets, giving the whole a light and airy texture. Unusually, the Kyrie belongs primarily to the four soloists, with chorus merely providing punctuation and emphasis. The light classical style is even more pronounced in the Gloria. The homophonic choral writing is underscored by a ‘Mannheim skyrocket’, the rapidly rising scale passage found so commonly in the early symphonic works of the Mannheim school. This musical style possessed an overwhelming energy, exuberance and almost uncontainable excitement. This is Schubert’s style here too some fifty years later.

The Credo, often the most solemn section of the Mass, is almost a dance. The triple time measure at first seems at odds with the metre of the words but what joy it brings to the words ‘creator of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible’. Contrast this with the next section, which speaks of the spirit made carnate, and crucifixion, where the harmonic language moves forward in time to wring full sentiment before returning to the joyful, chordal C major declaration that ‘on the third day he was resurrected and ascended into heaven.’

A rather thoughtful start to the Sanctus is another surprise but the solo soprano quickly dispels any doubt with her jubilant ‘Osanna in excelsis’. Schubert is best known for his tunes and so allows the soloist full measure in the Benedictus, which commonly in masses is in a slow duple time as here. This melody is perhaps unusual in its athleticism however. The solo voice has to navigate tricky rising and falling jumps without the least sign of strain or risk spoiling the calm for ‘blessed are they that go in the way of the Lord’. This is followed by a sinuous setting of the Agnus Dei and a final dance-like and precise ‘Dona nobis pacem’ as if to say that eternal bliss is a foregone conclusion.

Surely everyone recognises the opening of the Requiem in D minor K 626 of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart? The sombre basset horns over the plodding, brooding bass chords seem inseparable from our memory of the film Amadeus and all the myths surrounding this final work of the genius, cut down in 1791 in his 35th year. Yes, Mozart was troubled by the anonymous commissioner of the piece. Yes, as he approached death himself, he felt he was writing his own requiem. Yes, he died with the manuscript on his bed trying to give instructions about its completion. It is also true that several lesser composers had a hand in completing what he had started and who continue to this day. The version we perform tonight is the reworking by Beyer in 1983 to correct some of Mozart’s pupil Süssmayr’s worst errors.

But forget all of that. Whoever wrote what, when and why, this is a glorious and idiosyncratic work, by turns sumptuous and terrifyingly stark. It should be indulged, not analysed. We should subject ourselves both to the power and majesty of the music and the startling message of the catholic rite: through the pains and rage of death to eternal light, through tears and death’s dark vale to eternal rest, from prayers and supplications to the acknowledgement that the Lord will deliver us ‘as once promised to Abraham and his seed forever’.

Sara Kemsley