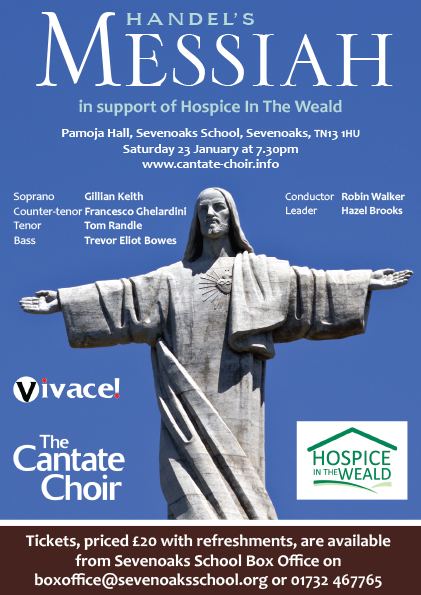

23rd January 2016

Pamoja Hall – Sevenoaks School

Handel composed the music for Messiah in twenty four days in August, 1741 – a speed of writing not unusual for him. Its first performance was given in Dublin – for reasons which need not detain us here – and takings for the concert benefited three charities. It was entirely appropriate, then, that Cantate chose this great oratorio for their showpiece concert and made it a benefit performance for Hospice in the Weald. Their target: £10,000.

Handel composed the music for Messiah in twenty four days in August, 1741 – a speed of writing not unusual for him. Its first performance was given in Dublin – for reasons which need not detain us here – and takings for the concert benefited three charities. It was entirely appropriate, then, that Cantate chose this great oratorio for their showpiece concert and made it a benefit performance for Hospice in the Weald. Their target: £10,000.

The choir which sang that first night in Dublin comprised 32 singers, about the same as the forces on which Cantate’s energetic conductor, Robin Walker, can call. The excellent instrumental ensemble Vivace!, with whom the choir collaborates from time to time, is also small in number but large and generous in music.

The wood-lined, open barn-like structure of the Pamoja Hall at Sevenoaks School (the word is Swahili, meaning ‘together’) has a feel of the Snape Maltings and this evening the combined forces of choir and small, elite orchestra filled it with a glorious diapason.

For this gala occasion, Walker secured the services of four soloists of singular distinction: Gillian Keith (soprano), Francesco Ghelardini (counter-tenor), Tom Randle (tenor) and Trevor Eliot Bowes (bass). Each of them sang with wonderful clarity of tone and diction, and a pure musicality which, allied to the verve and sonority of the Cantate choir, and the crisp and rounded playing of Vivace! made for a fine and memorable performance.

From the very opening, Walker conducting from the continuo console, the level of singing and playing was of the highest quality. (Handel had his own organ shipped to Ireland.) It was good to watch, too – never overlook the small drama of two Baroque trumpeters and timpanist gliding in noiselessly through a side door like stealthy autograph hunters during one movement to take up position for their contribution in the next number.

Fugal passages are where most choirs falter, if they lack cohesion, but Cantate have a choral discipline second to none. Moreover, they exhibit a fluent control of dynamic, tone and vocal coherence which comes only from alert intelligence, thorough-going rehearsal ethic and excellent pitching of notes.

There is no evidence that king George II was even present at the first performance of Messiah in London and the earliest mention of the audience standing during the Hallelujah chorus dates to 1756. However, when the audience in Pamoja stood up together this evening, there was a palpable thrill in the hall.

At the end of the interval – glasses of English vineyard fizz and a second visitation of raffle ticket sellers in the foyer – the choir master triggered another thrill in the hall: the evening had raised more than £10,000. Hallelujah.

When Handel reached Fishguard en route to Ireland, he dined at an inn where he ordered ‘dinner for two’. When the landlord asked him where his dining companion was, the composer replied: ‘I am der two.’ Gargantuan appetite, superabundant musical genius and sponsor of another triumph for Cantate.

Graeme Fife