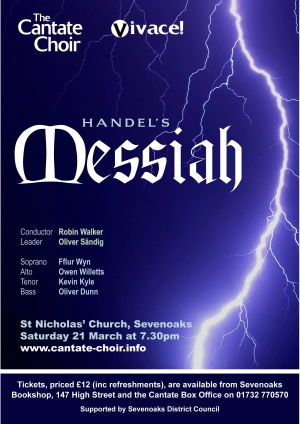

I know that my Redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth. And though worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God. Book of Job xix:25-26

These words, which begin Part III of the mighty oratorio ‘Messiah’, were inscribed on George Frideric Handel’s tomb in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey when he died in 1759. This aria, written in the optimistic, bright and certain key of E major, opens with two notes (dominant rising to tonic) and sums up for me the entire piece; without any shadow of a doubt, with no possibility for confusion, Handel says, ‘I believe’. He genuinely felt that the whole piece was given to him by God. As Patrick Kavenaugh records in his Spiritual Lives of the Great Composers, Handel said to his bemused servant “I did think I did see all Heaven before me, and the great God Himself.” Handel had just finished writing a movement that would take its place in history as the Hallelujah Chorus.

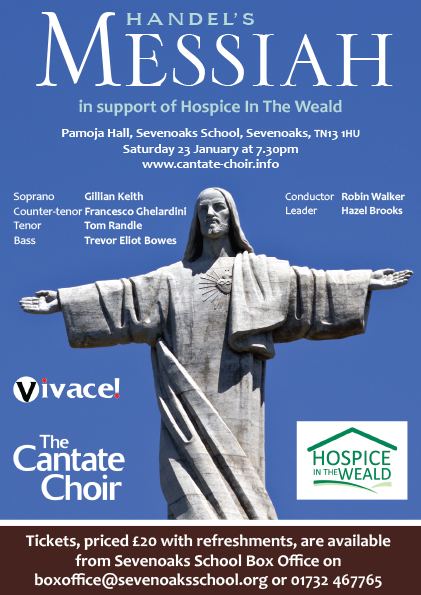

How fitting it is that tonight’s performance is in aid of The Hospice in the Weald. In 1741, two letters arrived, which changed Handel’s position and musical history forever. First came an invitation from the Duke of Devonshire to come to Dublin and provide a series of benefit concerts ‘For the relief of the prisoners in the several gaols, and for the support of Mercer’s Hospital in Stephen Street, and of the Charitable Infirmary on the Inn’s Quay’. Then, a letter arrived from Charles Jennens, a literary scholar and editor of Shakespeare’s plays, who had previously written libretti for Handel. The letter contained Old and New Testament texts, which Handel read and re-read and was so moved that he immediately embarked on writing a sacred opera using them. Messiah premiered on April 13, 1742 in Dublin as a charitable benefit, raising 400 pounds and freeing 142 men from debtor’s prison. It has not been out of performance for a single year since, a record unsurpassed by any other classical work. It was performed again and again for charitable concerts and Handel would not take a penny from the ticket sales, believing that God, not he, had written the piece. At his death, he bequeathed the manuscript and parts to the Foundling Hospital, founded by Thomas Coram in 1739, which continues to benefit to this day from performances of Messiah. Charles Burney, the 18th century music historian, remarked that Handel’s Messiah “fed the hungry, clothed the naked, and fostered the orphan.”

Why then, is Messiah such an enduring and monumental piece? Why is it performed every year all over the world? Why are there choral societies committed to performing nothing else? It is not a typical oratorio; there are no named characters, no plot and no narrative. There is no drama of action or personalities and no dialogue. Our usual thirst for soap opera shenanigans will not be satisfied here. So why do we keep coming back for more?

For one thing, it is a work, whose three parts, take in the entire sweep of the traditions and beliefs of the Christian faith and follows the liturgical year:

- Part I- Prophecy of Salvation, the birth of Christ Jesus (Advent, Christmas)

- Part II- Crucifixion and Death (Lent, Easter, Ascension, Pentecost)

- Part III- Resurrection and the promise of eternal life for believers (End of year and end of time)

The second reason for its recurrent popularity is that it is simply full of good tunes and rousing choruses, which enable us as Everyman to grasp something of the ineffable mysteries of these sacred texts and to go away feeling spiritually uplifted regardless of our beliefs and understandings.

The main reason, however, has to be the sheer genius of the man (or perhaps it really was his divine inspiration). Handel paints the texts so vividly and gloriously that it seems impossible not to be profoundly moved by each and every aria, chorus and instrumental interlude.

The libretto by Jennens is also monumental and scholarly. The texts are compiled from the Bible: mostly from the Old Testament of the King James Bible, but with several psalms taken from the Book of Common Prayer. He takes lines from here and there to construct ‘scenes’ of meditation upon aspects of the Messiah. We perform Part I complete, which takes us through the surprisingly restrained prophecies and announcements of Christ’s coming, through the excitement of the birth (For unto us a child is born), the appearance of angels before the shepherds (Glory to God) and on to the great optimism of the believers (Rejoice greatly, He shall feed his flocks).

Part II deals with Christ’s sufferings and betrayal. We cut numbers 27-37, which deal with the actual crucifixion and reception into Heaven, and take up the scene with the moving reaction to his death (How beautiful are the feet) and the gradual spreading of the gospel despite the world’s rejection (Hallelujah). Part III is also shortened to focus on the certainty of believers that the Redeemer is still very much alive in men’s hearts and that when ‘The Trumpet shall sound’ death and sin will be conquered and we will find ourselves with God. The final chorus maintains the focus solely on the Messiah, not the unworthy mortals who usually receive some absolution at the end of such works. “Worthy is the Lamb that was slain and hath redeemed us to God by His blood, to receive power, and riches, and wisdom, and strength, and honour, and glory, and blessing. Blessing, and honour, and glory, and power, be unto him who sitteth upon the throne and unto the lamb for ever and ever, Amen.”

Sara Kemsley