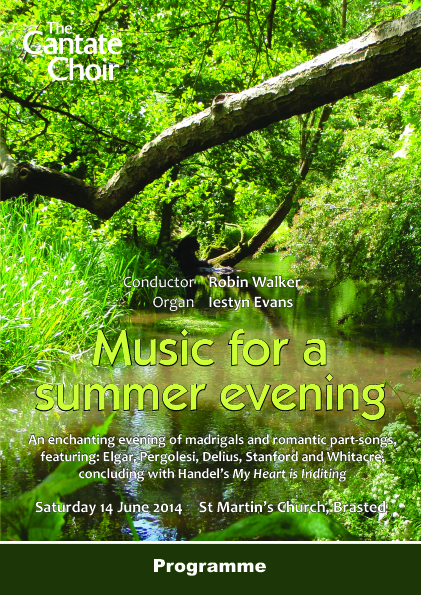

7.00pm, Saturday 14 June – St Martin’s Church, Brasted

Soloists

Robin Walker – Conductor

Iestyn Evans – Organ

Programme

T. Campion 1557—1620 – Never weather-beaten sail

J. Bartlet fl. 1606—10 – Of all the birds that I do know

R. Jones fl. 1597—1615 – Farewell, dear love

G. Finzi 1901—56 – My spirit sang all day

E. Elgar 1857—1934 – As torrents in summer

C.H.H. Parry 1848—1918 – Music, when soft voices die

C.V. Stanford 1852—1924 – The blue bird

F. Delius 1862—1934 – To be sung of a summer night on the water (two unaccompanied part-songs)

G.B. Pergolesi 1710—1736 – Magnificat

A. Hollins 1865—1942 – A Trumpet Minuet

J. Jongen 1873—1953 – Petite Prélude

M. Lanquetuit 1894—1985 – Toccata

Eric Whitaker b. 1970 – Sleep

G.F. Handel 1685—1759 – My heart is inditing

Programme notes

Music, when soft voices die, vibrates in the memory Percy Bysshe Shelley

The theme of this poem, set to music by Parry among several others, is the ability of sounds, sights, smells and emotions to linger and be stirred in the memory long after the fact. In some ways a thread of memories is stirred by tonight’s programme but it is an uncertain and discontinuous one. It is a trail which we now lose and then rediscover in another place and another time.

The first half may be said to encompass two periods of English Renaissance, the first in the 16th and 17th century with the flowering of madrigals, ayres and anthems and the second in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when composers stepped once more into the light of European recognition. England under Elizabeth I and James I provided a period of peace and encouragement for the arts. In a list of 67 composers from this time, 24 of them are names you will probably know or who made pieces you would recognise if you heard them. Then the land fell largely silent.

In 1904, the German critic Oskar Schmitz described Britain as a ‘land without music’. However, there was already a revival afoot in music making at all levels. There was huge growth in amateur and professional choirs and orchestras and we remain unsurpassed in our national quality of performance to this day. The Royal College of Music was expressly set up ‘to rival the Germans’ and produced the leaders of this new movement in Parry and Stanford. What they started, the likes of Elgar, Finzi, Vaughan Williams, Holst, Walton and even Delius continued. ‘Fritz’ Delius was considered too German to count but ironically it is his music which captures the idyllic English countryside and lazy summer days better than anyone’s.

In the first English Renaissance, you could argue that the poetry was not great but the musical settings often were. Do we remember George Gascoigne, the poet Thomas Campion or anon.? Unlikely! The words are often obscure and susceptible to erotic interpretation as with John Bartlet’s Philip the sparrow, who cries yet, yet, yet, yet…..! By the time of the second Renaissance, English Literature is a major world subject with a long unbroken tradition. Parry and Stanford moved in the same circles as Robert Bridges, Mary Coleridge, Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Christina Rossetti and Alfred Lord Tennyson.

Tackling their poetry must have been both privileged and intimidating. Later generations of composers like Finzi and Delius had some latent memory for word setting built into their DNA, which makes their songs generally more fluid and natural. ‘My spirit sang all day’ is No.3 of Finzi’s Seven Poems by Robert Bridges. It captures the emotional arc of the lover’s joy in just 44 bars of sublime music. ‘The Blue Bird’ is a setting by Stanford of a Mary Coleridge poem. She was grand-niece to Samuel Taylor Coleridge and her father Arthur Duke Coleridge founded the London Bach Choir with Jenny Lind in 1875. Robert Bridges, the Poet Laureate, described her poems as ‘wondrously beautiful… but mystical rather and enigmatic’. Stanford’s setting still seems experimental today and hard to pull off but it paints the most wonderful image of summer blue all around you.

For the second half of our concert, we step in from the fertile territory of our green and pleasant land – quite literally if weather has permitted the first half to be outdoors. We have already seen that pupils will usually surpass their teachers but it comes to something when a pupil passes off his teacher’s piece as his own. Well, in fairness, it was not Pergolesi himself but a much more recent musicologist who wrongly ascribed Francisco Durante’s ‘Magnificat in Bb major’ to Pergolesi and the myth persists despite most scholars disagreeing. Whoever wrote it, it is typical of the School of Naples in the seventeenth century, where both men worked. Technically competent, it is an unsentimental setting of Mary’s song of gratitude, once she has come to terms with being single, pregnant, poor and homeless. She realizes that she has effectively been crowned the queen of heaven, mother of God, ‘from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed’.

Eric Whitacre is an American composer and something of a Gareth Malone of the internet. His choral pieces draw on the long back catalogue of English language word setting. They are understated, direct, yet with a personal voice. What he does with his pieces is to use cutting-edge technology to bring ordinary people together from around the world in performance. Do visit his website www.ericwhitacre.com and experience his virtual choir performances of ‘Sleep’ and other works or listen to him on the global TED website (www.ted.com), which brings ideas together from Technology, Entertainment and Design.

This piece started out as a setting of Robert Frost’s poem ‘Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening’ but copyright issues meant he could not use the words so he asked a friend to write new lyrics and, personally, I think they are better.

And so we come to the one strong voice in the Land without Music, which sang out between one renaissance and the next and, blow me down, he was German and this piece was written for the coronation of a German! Of course, another strong theme for this land of ours is to welcome immigrants and adopt them as our own. It is therefore entirely fitting for Handel to take words set by Purcell at the Coronation of James II in 1685 (the year of Handel’s birth but that is nothing to do with anything) and use them for his own setting at the Coronation of George II in 1727. ‘My heart is inditing’ is the fourth Coronation Anthem and the last in the ceremony when the queen is crowned, in this case Charlotte. The words from Psalm 45 and Isaiah 49 extol the virtues and rank of women. ‘Kings’ daughters were among thy honourable women’ and the queen is as ‘a nursing mother’ to the nation. The Cantate Choir sang Purcell’s version in June 2009 alongside Parry’s Songs of Farewell, settings of English poets including Thomas Campion….. ah, there go those vibrations again!

Sara Kemsley