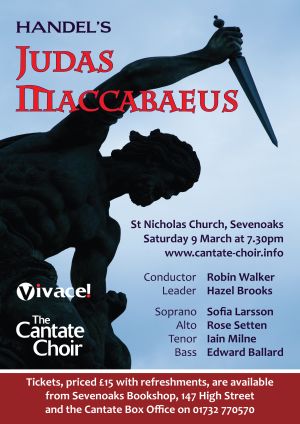

7.30pm, Saturday 9 March 2013 – St Nicholas Church, Sevenoaks

Soloists

Hazel Brooks – Leader

Sofia Larsson – Soprano

Rose Setten – Alto

Iain Milne – Tenor

Edward Ballard – Bass

Review

Graham Fife – Reviewer

Programme

Handel – Judas Maccabaeus

Programme notes

Toughness found fertile soil in the hearts of Palestinians, and the grains of resistance embedded themselves in their skin. Susan Abulhawa, Mornings in Jenin.

For more than three thousand years, the area of modern Israel and Palestine has been divided, disputed, conquered and restored again and again and again. This ancient land of the ‘12 tribes of Israel’ became the two kingdoms of David and Solomon in the 10th century BC. When Alexander the Great died in 323 BC, his empire was divided and Ptolemy took Egypt and the lower regions, while Seleucis gained Babylon and Syria. By 198 BC the Syrians had taken Palestine and with it Jerusalem. The Jews suffered much hardship as Antiochus IV sought to impose Hellenistic culture and religion on the people. By 167 BC, all Jewish rites were forbidden and the Temple sacked.

Mattatias, a priest from Jerusalem, led the first rebellion, which was continued by his sons the Maccabees: John, Simon, Judas, Eleazer and Jonathan. Morell’s libretto for Handel’s oratorio starts here, with the death of Mattatias; “Mourn, ye afflicted children, your sanguine hopes of liberty give o’er” sings the chorus to a weary and resigned C minor accompaniment.

Part One deals with the aftermath of Mattatias’ death. Simon urges the Israelites to put their faith in God and seek a new leader. He then claims that God has chosen his brother Judas for the job. Judas steps up immediately and calls on the people to take inspiration from the struggles of their forefathers and their just cause. The Israelites offer prayers for their new leader and for the return of liberty. ‘Disdainful of danger’ they prepare for battle, ‘resolved on conquest or a glorious fall’.

Like all the best dramas of the past, the action then takes place offstage and out of sight. Would that modern film makers could show similar restraint! Part Two opens with the Israelites returning from battle pumped up with their victory, “Fall’n is the foe!” they shriek in every possible permutation of this little phrase. Like a returning football crowd they are full of Judas’ performance on the field. Judas accepts their tributes, while modestly thanking God for his triumph. But news arrives from a Messenger that “new scenes of bloody war in all their horrors rise”. General Georgias is marching from Egypt. Immediately, the people are thrown back into despondency and the Israelitish Woman, a device used throughout to represent the mood of the people, sings “Ah, wretched Israel” in C minor again – back to square one! Once again, Simon exhorts them to have faith in God and Judas calls on them to fight. He promises to restore the temple and the people vow never to worship heathen idols, “We never will bow down to the rude stock of sculptured stone”.

Part Three opens with a Festival of Thanksgiving, for the Temple has been regained and reconsecrated. This first festival has continued down the years as Hanukkah, the Festival of Lights, in the Jewish tradition. The Messenger returns with more news of Judas’ victories, this time at Capharsalama. Judas returns in triumph and is greeted enthusiastically by his fellow people. The famous choruses “See, the conqu’ring hero comes” were not in Handel’s original 1747 score but he borrowed them from his oratorio Joshua for his 1758 revision. Judas asks the Israelites to remember the fallen heroes, especially his brother Eleazer who was killed when a war elephant fell on him. In the final scene, Eupolemus, their ambassador, returns from Rome with a treaty, which guarantees the protection of Judea as an independent nation. At last, the people can look forward to “Endless fame” as says the Israelitish Man and “O Lovely Peace” as sings the Israelitish Woman. “Hallelujah”, of course, says Handel.

Fame certainly came to the Maccabees. For over one hundred years, scholars have searched for the lost tombs of the Maccabees and in 2012 using latest radar techniques, they think they may have found them. The city of Mod’in, now in Israel and once home of the Maccabees, celebrates Hanukkah every year with particular fervour. And Handel has certainly done justice to their story in this superb oratorio. But lasting peace, as we all know, still seems a long way off for this troubled land.

Handel composed this oratorio in 1746 based on a libretto written by Thomas Morell. The oratorio was devised as a compliment to the victorious Prince William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, upon his return from the Battle of Culloden (16 April 1746), the last pitched battle on British soil. It was first performed at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden. Morell was a saddler’s son but educated at Eton and Trinity College Cambridge. He was a religious scholar and provided several libretti for Handel. Both Handel and Morell moved in illustrious circles at this time having royal, artistic and literary connections. It was intended that the public saw parallels between Judas’ story and the heroism of the Duke.

Handel has always been revered by other composers even though his popularity with audiences has waxed and waned over the centuries. J S Bach desperately wanted to meet him and Mozart said of him “Handel understands affect better than any of us. When he chooses, he strikes like a thunder bolt.” Beethoven emphasised above all the simplicity and popular appeal of Handel’s music when he said, “Go to him to learn how to achieve great effects, by such simple means”. Handel, as a successful society composer, could afford the luxury of experimentation with his orchestras and introduced many new and varied instruments and combinations into both his operas and oratorios. In Judas Maccabeus he uses both recorders and flutes, even though the Baroque flute was wooden and softly spoken too. Horns and trumpets are used sparingly despite the themes of battle and rebellion. Brass instruments are designed for celebration and triumph in Handel’s view. Bassoons are increasingly becoming permanent fixtures and allowed more independence than simply copying the bass line in the loud bits.

Our performance tonight with Vivace will be at Baroque pitch since the instruments they play are originals or replicas of that time. But what is ‘Baroque pitch’? Pitch is measured in hertz and is standardized purely for convenience. Around the world today the A in the treble stave is fixed at 440Hz so that performances and recordings will be the same wherever you go. This is known as Concert Pitch. However, in the Baroque Era, pitch levels as high as A-465 (17th century Venice) and as low as A-392 (18th century France) are known to have existed. String players could easily re-tune but wind players could be limited to playing only with people from their own area. Modern ‘Baroque pitch’ is generally standardized as 415hz, which is about a semitone below Concert pitch. The sopranos and tenors love it but the altos and basses can find themselves going down where they have rarely been before!

Sara Kemsley