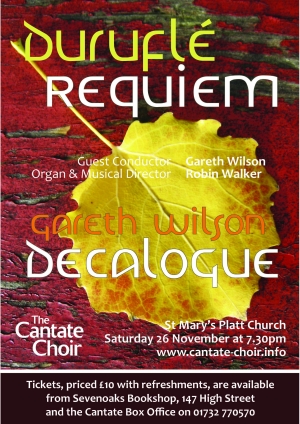

7.30pm, Saturday 26 November, 2011 – St Mary’s Platt Church, Nr Borough Green

Soloists

Gareth Wilson – composer & conductor

Nicholas O’Neill – organ

Programme

Gareth Wilson – Decalogue

Duruflé – Requiem

This concert included Gareth Wilson’s first performance outside London of ‘Decalogue’.

Performing new music, and working with composers is a real thrill for musicians: getting the music ‘hot off the press’. The Cantate Chamber Choir worked with Gareth Wilson, conductor, composer, theologian and educator, preparing his new work ‘Decalogue’ for their concert on Saturday 26th November in the Parish Church of St Mary Platt.

The work, sets biblical texts from both the old and new testaments, to music as a set of eleven motets for choir and organ. Each text is chosen to highlight one of the Ten Commandments, with the eleventh movement being the words of Jesus; “I give you a new commandment”.

The composer, Gareth Wilson, conducted the work and the choir’s musical director, Robin Walker, played the substantial organ accompaniment.

For the second half of the concert Robin conducted the choir as they performed one of the choral repertoire’s most loved works: Maurice Duruflé’s ‘Requiem’, with its haunting ‘Pie Jesu’ and heavenly ‘In Paradisum’.

Programme notes

‘Everyone ought to bear patiently the results of his own conduct‘. Phaedrus (1st century AD)

Both of tonight’s composers bring to their work great attention to detail and a theological interest, which adds layers of meaning to otherwise traditional techniques. Both have served as directors of music at distinguished capital city churches: Duruflé at St. Etienne du Mont in Paris and Wilson at Christ Church, Chelsea. Maurice Duruflé was such a perfectionist that he only allowed around a dozen works to be published and even then, he often tinkered with them after publication. He studied the organ and then composition at the Paris Conservatoire and followed a career as an organist in partnership with his organist wife, Marie-Madeleine Chevalier- Duruflé, until a serious car crash in 1974 left him almost completely housebound. He died in 1986.

Gareth Wilson’s Decalogue is a working of the Ten Commandments, which received its first performance in 2010 at King’s College Chapel, London, where Gareth is also choral director. The work merits the detailed reading of the composer’s own notes, which are reproduced with this programme, but for those wanting the short guide, some essentials follow here. Each commandment is a treatment of a biblical text, which is in some way an illustration of humanity’s ability to get it wrong – over and over again. Gareth is interested in our tendency to make pronouncements and judgements upon other people, without looking at ourselves or improving our self-knowledge. The bible, he asserts is ’if nothing else, an exploration of what it is to be human’.

He uses several conventions throughout the work to help our understanding of the texts and the theological points he raises. He has set Latin versions of all the biblical texts, an unusual choice given 400 years of the King James’ version of the Bible in English. The voice of God is invariably represented by the choir singing in octaves. Where there is harmony, this is humanity, or sometimes Christ, speaking. He also uses melodic fragments to represent ideas like Good and Evil, which occur in several movements and contribute to that sense of ‘will we never learn?’ which seems to pervade the texts.

Nos. I and X deal with Man overreaching himself with the expulsion from Paradise and the building of the Tower of Babel. III, IV, VI and VII all remind us of the hypocrisy of those in authority who pass down judgments when their own actions leave much to be desired. II, V and IX deal with the frailty of the human will, which has too little faith, a lack of appreciation for what we have and a lack of backbone when times get tough. No. VIII ‘You shall not steal’ treats the Judgement of Solomon. It is a story retold by Bertolt Brecht in the Caucasian Chalk Circle. Two mothers argue over a child they believe to be theirs. The true mother is the one prepared to give up her child rather than harm him. Wilson adds an eleventh commandment, just as Christ did. It is sung unaccompanied in English, “I give you a new commandment that ye love one another. As I have loved you, so must ye love one another.”

The Requiem Mass of Duruflé was written in 1947 and follows in a long line of settings all the way back to the plainchant version set down by Pope Gregory in the sixth century. As a choirboy at Rouen Cathedral, Duruflé became very familiar with the transcriptions of Gregorian chant and all nine movements of the Requiem, as well as others of his works, make extensive use of the original chants. Whereas, most previous settings of the Mass for the Dead make full use of the dramatic elements of the words, Duruflé, like his compatriot Fauré before him, leaves out the long Dies Irae, which deals with all the fire and brimstone stuff. He inserts instead the Pie Jesu and ends with In Paradisum. This, combined with the flowing plainchant rhythms and limpid, impressionist harmonies, gives the piece a contemplative and encouraging character and stands in contrast with the works of Mozart and Verdi for example.

The composer produced three versions of the Requiem, with organ or orchestral accompaniment, with and without soloists. Our version is the most pared back and, some might say, most in keeping with its monastic roots. The opening Introit is sung very gently by the men over a moto perpetuo figure on the organ. The women, as ever, are being ethereal. The Kyrie builds a more elaborate polyphonic texture from the plainchant opening, which builds and builds so that every voice is soaring in luscious harmony.

The third movement, Domine Jesu Christe, prays for release from the jaws of hell. After a hesitant start, the music is more angular and chordal. The keys rise higher and higher as the desperate souls beg not to end up in the abyss. This all changes as first the ladies and then the men remind God of his promise to spare Abraham and his seed.

Sanctus is very reminiscent of Faure’s treatment, soft slow chords over constantly moving arpeggio figures in the accompaniment and the effect is almost the same: a static (even ecstatic) moment of peace. This is followed by Pie Jesu set for Mezzo-soprano solo, a heartfelt prayer for eternal rest. The calm seems to continue in the Agnus Dei but appearances are deceptive here. An agitated little accompaniment sits underneath the elegiac phrases throughout. The phrases of the singers are short and uncertain and the effect is heightened when the altos follow the sopranos in a tight little canon. However, all consternation dissolves at the words ‘dona eis requiem sempiternam’ (Grant them eternal rest).

The seventh movement Lux Aeterna has a lucidity and charm which is reminiscent of some modern carol settings with a simple high melody over hummed chords. The contrast then in the next movement Libera Me is extraordinary. Trombone and trumpet sounds signal the Last Judgement and the voices of the men sound as if they are calling from the deep ‘release me, Lord, from eternal death’. This movement is theatrical, albeit a restrained treatment, in its setting of the words. Finally, we glimpse In Paradisum among the angelic chorus. Long held notes suspend us in the stratosphere and the final chord remains unresolved. We must wait a while longer, it seems, patiently considering our own conduct.

Sara Kemsley