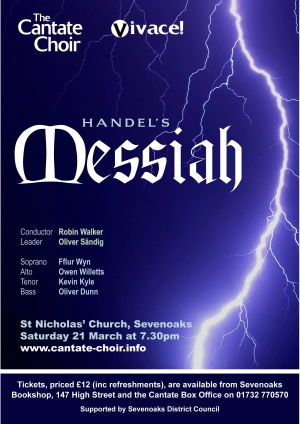

7.30pm, Saturday 21 March 2009 – St Nicholas’ Church, Sevenoaks

Soloists

Fflur Wyn – soprano

Owen Willetts – alto

Kevin Kyle – tenor

Oliver Dunn – bass

Oliver Sandig – leader

Review

Steve Coles – review

Programme

Handel – Messiah

Programme notes

2009 is the 250th anniversary of Handel’s death, and what better way to celebrate the work of England’s most famous and enduring composers than to hear Messiah, the dramatic musical drama of Jesus’ life.

Handel famously composed Messiah in only a few hectic days, creating a work which has been performed every year since it’s first performance, a unique achievement. It is no surprise the work has found such fame, containing as it does so many memorable pieces, including possibly the most famous and recognisable of any, the Hallelujah chorus. Messiah is really Opera for the church, and the drama of the narrative carries us through chorus, aria and recitative for a thoroughly engaging and entertaining evening.

In a small London house on Brook Street, a servant sighs with resignation as he arranges a tray full of food he assumes will not be eaten. For more than a week, he has faithfully continued to wait on his employer, an eccentric composer, who spends hour after hour isolated in his room.

Morning, noon, and evening the servant delivers appealing meals to the composer and returns later to find the bowls and platters largely untouched.

Once again, he steels himself to go through the same routine, muttering under his breath about how oddly temperamental musicians can be. As he swings open the door to the composer’s room, the servant stops in his tracks.

The startled composer, tears streaming down his face, turns to his servant and cries out, “I did think I did see all Heaven before me, and the great God Himself.” George Frederic Handel had just finished writing a movement that would take its place in history as the Hallelujah Chorus.

(from Spiritual Lives of the Great Composers by Patrick Kavanaugh)

George Frederic Handel was born in Saxony in Germany in 1685 but from 1712 he resided almost solely in England, patronised by Kings George I and II so that he has rather been adopted as an English composer (and, heaven knows, we have few enough great composers as of right!) He had enjoyed enormous critical and financial success as a composer of operas but by 1741 his fortunes had fallen mightily. His operas were regarded by many as scurrilous and the Covent Garden Theatre, which he ran, a ‘den of rascals’. He was close to ruin and the debtors’ prison.

Out of the blue, two letters arrived, which changed Handel’s position and musical history forever. First came an invitation from the Duke of Devonshire to come to Dublin and provide a series of benefit concerts ‘For the relief of the prisoners in the several gaols, and for the support of Mercer’s Hospital in Stephen Street, and of the Charitable Infirmary on the Inn’s Quay’. Then, a letter arrived from Charles Jennens, a literary scholar and editor of Shakespeare’s plays, who had previously written libretti for Handel. The letter contained Old and New Testament texts, which Handel read and re-read and was so moved that he immediately embarked on writing a sacred opera using them. Messiah premiered on April 13, 1742 in Dublin as a charitable benefit, raising £400 and freeing 142 men from debtor’s prison. It has not been out of performance for a single year since, a record unsurpassed by any other classical work.

Handel believed that God spoke to him and required him to write the piece down. It was performed again and again for charitable concerts and Handel would not take a penny from the ticket sales, believing that God, not he, had written the piece. At his death, he bequeathed the manuscript and parts to the Foundling Hospital, founded by Thomas Coram in 1739, which continues to benefit to this day from performances of the Messiah. Charles Burney, 18th century music historian, remarked that Handel’s Messiah “fed the hungry, clothed the naked, and fostered the orphan.”

Why then, is Messiah such an enduring and monumental piece? Why is it performed every year all over the world? Why are there choral societies committed to performing nothing else?

For one thing, it is a work whose three parts take in the entire sweep of the traditions and beliefs of the Christian faith:

Part One — Prophecy of Salvation, the birth of Christ Jesus

Part Two — Crucifixion and Death

Part Three — Resurrection and the promise of eternal life for believers

A complete performance requires nearly three hours and therefore it is common to hear cut versions, particularly those around Christmas time, which focus on Part I with other good bits thrown in.

The second reason for its recurrent popularity is that it is simply full of good tunes and rousing choruses, which enable us as Everyman to grasp something of the ineffable mysteries of these sacred texts and to go away feeling spiritually uplifted regardless of our beliefs and understandings.

The main reason, however, has to be the sheer genius of the man (or perhaps it really was his divine inspiration). Handel paints the texts so vividly and gloriously that it seems impossible not to be profoundly moved by each and every aria, chorus and instrumental interlude. The contents page reads like a Classic FM 50 greatest hits countdown and this is no accident. Each and every piece is immaculately conceived in melodic, harmonic and textural terms and thus is as unforgettable as Michaelangelo’s David or Da Vinci’s Last Supper. But theirs were single pieces and this is a mighty collection of such works.

To begin the countdown, who can forget the affirmative ‘And the Glory, the Glory of the Lord’ as it strides upwards in A major to its home note? Or, after the ferocious portent of his coming ‘as a refiner’s fire’, the chorus delicately sprinkling water upon us in ‘And he shall purify’? Next, ‘For unto us a child is born’ uses the melody of a love song previously used in one of Handel’s operas and is simply the joyous babble of the christening party. In Part II, can there be a more gut-wrenching portrayal of misery and betrayal than the aria ‘He was despised and rejected of men’? It relentlessly pursues the falling semitone, long acknowledged to be as close to a human sigh as mere notes can be.

We all know the Hallelujah Chorus and it is traditional to stand for it as King George II spontaneously did when he first heard it. But it is the words which begin Part III, ‘I know that my Redeemer liveth’, which were inscribed on Handel’s tomb in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey when he died in 1759. Written in the optimistic, bright and certain key of E major, the opening two notes (dominant rising to tonic) sum up for me the entire piece; without any shadow of a doubt, with no possibility for confusion, Handel says, ‘I believe’.

Sara Kemsley