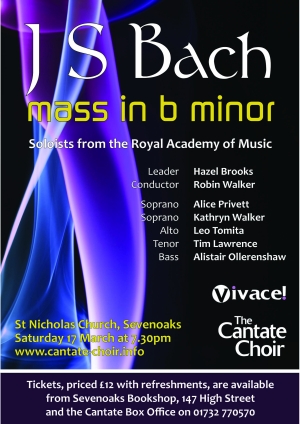

7.30pm, Saturday 17 March 2012 – St Nicholas Church, Sevenoaks

Soloists

Alice Privett – Soprano

Kathryn Walker – Soprano

Leo Tomita – Alto

Tim Lawrence – Tenor

Alistair Ollerenshaw – Bass

Hazel Brooks – leader

Programme

Bach – Mass in B minor

Programme notes

“The aim and final end of all music should be none other than the glory of God and the refreshment of the soul.” Johannes Sebastian Bach

The Mass in B Minor is the only full mass or missa tota, which Bach wrote and it was also his last major composition. Working as a Lutheran composer in eighteenth century Germany, it was the short mass consisting of the Kyrie and Gloria, which was used for church services. The B minor mass was pulled together from movements written earlier in his life: the Kyrie and Gloria in 1733 for the Elector of Saxony, the Sanctus in 1724 and the Qui tollis based on a cantata chorus of 1714. To these he added newly composed sections. There is speculation that Bach wrote this full mass, not for liturgical use, but as a statement of Christian beliefs for all people and for all time.

Musically, it represents the pinnacle of High Baroque style, a style which had already given way to the simpler galant style of Bach’s own sons and composers such as Stamitz, Quantz, Couperin and Telemann. This clean, clear homophonic style with easy melodies and gentle decoration laid the foundations for the mature Classical style of Haydn and Mozart by the end of the century. In this sense, Bach was already behind the times and his music all but disappeared until the nineteenth century rediscovery of this hardworking and unassuming genius.

“It’s easy to play any musical instrument: all you have to do is touch the right key at the right time and the instrument will play itself.” Try telling that to the orchestral musicians who accompany our performance this evening. They have committed years to mastering their instruments and hours to maintaining their period versions in good playing order. Bach’s musicians must have been no less skilful as the orchestra plays a vital role in securing Bach’s vision and technical brilliance. The different colours of each movement, and of sections within movements, are created by absolutely unique combinations of wind, brass and string timbres. This is quite literally his canvas upon which the words of the mass are layered.

The opening movement, Kyrie eleison (Lord have mercy) sets up all that is to follow. A short, chromatic declamation in B minor is followed by an instrumental prelude of dark and subdued nature from strings and oboe d’amore, an alto-voiced oboe. The Kyrie proper then comes in the form of a 5-part fugue but one with such a long subject melody and at a gentle walking pace so that all you notice is the luxurious interlacing of parts and none of the theoretical genius behind its composition. This is like mining a seam of unspeakably gorgeous Belgian chocolates, the flavours constantly changing, some a little surprising. When it suddenly ends, you are already looking for the next layer.

Christe eleison (Christ have mercy) is in D major and sung elegiacally by two soprano soloists over a typically busy string and continuo accompaniment. The traditional repeat of Kyrie eleison is another fugue, this time in 4-parts, that is four voice parts. This one is a sinuous and slippery character full of shifting semitones and is another third higher in F sharp minor.

The Gloria is split by Bach into nine sections each with its own character arising from careful selection of voices, keys and instrumentation. It begins with a dancing, triple time piece with glittering flutes and trumpets adding to the joy. The changes of gear on occasion are unsettling but the words are usually in charge, for Bach is the master of imagery through music. For example, the dainty flute and violin accompaniment for Domine Deus is a crystalline sorbet compared with the fiddly and nervous soufflé for the solo soprano in Laudamus Te or the pensive alto solo with accompanying oboe d’amore for Qui sedes (who sitteth at the right hand).

The bass aria, Quoniam tu solus sanctus (Thou art the only holy one) seems to argue this theory; with hunting horn and two bassoons, it is almost comically absurd. But surely this is Bach at the height of his powers enjoying a hand-stopped natural horn and the human bass voice performing near-impossible leaps and wriggles to express the one, almighty, most high. This is exhibition stuff from an old master.

The next major section is the Nicene Creed (I believe in one God, Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth). This is also split into nine sections beginning with a fugue for choir based on the original Gregorian chant for Credo in unum Deum. There is great energy in these movements and a sureness of touch. For example, the duet of the third movement, which is written like a round just one beat apart, still sounds completely natural and assured despite the compositional dexterity.

The word-painting of the next three movements speaks for itself in the descending phrases for ‘was made flesh’, the heart-rending Crucifixus and the elation of ‘on the third day, rose again’. The bass aria which follows is this time genteelly pastoral with oboes and continuo for a dignified setting of ‘the holy spirit, Lord and giver of life’. The Creed ends with the longest movement, Confiteor unum baptisma (We believe in one holy catholic and apostolic church). This section looks forward to the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection after death and life ever after. The full forces of choir and orchestra are brought to bear in this joyous affirmation of faith.

Much of the mass so far has been for 5-part chorus, the extra soprano line giving light and brilliance to the textures. From the Sanctus to the end, Bach builds the choral forces more and more strongly. Holy, Holy, Lord God Almighty, is for 6-part choir, the extra alto line enriching the middle register and providing glue in the oscillating triplet lines. It also means that a 6-part fugal section is much busier to describe Pleni sunt coeli (the heavens are full of his glory), trumpet-blowing cherubim flitting all over the place.

The final group of movements, Osanna, Benedictus, Agnus Dei and Dona Nobis Pacem, opens with the only unison and unaccompanied cry of the whole work. In D major, the most nearly-related key to the pervading B minor, this is unequivocal joy and does little to prepare us for the Agnus Dei (Lamb of God, have mercy upon us). In G minor (two flats instead of two sharps), this is musically the most distant key of the entire work. The yearning phrases of the alto soloist are almost painful, set against the hesitant but constant bass line. Nearly every long note in the entire movement is a dissonance waiting to be soothed.

Unusually, Bach takes the final words of the Agnus Dei (grant us peace) and treats them as a final movement, a straightforward, last short fugue in an affirmative D major on a rising theme. Ite, missa est, the priest would say by way of dismissal. Bach seems to be telling us to do likewise, our souls refreshed.

Sara Kemsley