Tuesday 31 May 2011 – Methodist Church, Florence, Italy

Wednesday 1 June 2011 – 13th century church of Saint Augustine, San Gimignano, Italy

Thursday 2 June 2011 – La Badia Fiorentina (Florence Abbey), Florence, Italy

7.30pm, Thursday 16 June – St Margaret Patten’s Church, City of London

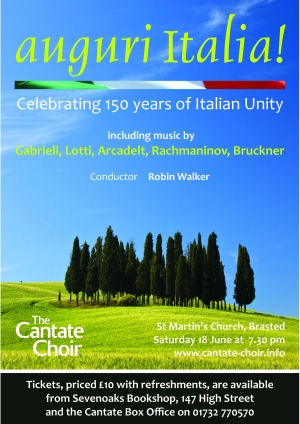

7.30pm, Saturday 18 June – St Martin’s Church, Brasted

On 30th May, ‘Cantate’ set off for Florence, for a week of performances in Tuscany. They take with them a delightful summer programme celebrating 150 years of Italian Unity and will return to England for their UK concerts in London and finally Brasted. These ‘a capella’ concerts will feature music from the 15th to the 20th century, with a particular focus on Italian and English composers, including Giovanni Gabrieli, Antonio Lotti, Charles Wood, William Harris, John Dowland and Edward Bairstow. The concert will finish with Joseph Rheinberger’s wonderful Mass in E flat major.

In Florence, all three concert venues are ancient churches with rich histories. The first is the Methodist Church in Florence, built in the 12th Century as a monastery, and the place where the clavichord was perhaps invented. It is also only a few doors away from the palazzo in which dramatic recitative was first heard, the birthplace of modern operatic style. The church is only a few hundred yards from the church of Santa Croce, where Rossini is buried, whose Messe Solennelle the choir performed in March this year.

The 13th century church of Saint Augustine in the UNESCO World Heritage town of San Gimignano, south of Florence, is the choir’s second port of call. San Gimignano is famous for its many tall towers, used to dry long lengths of cloth dyed with local saffron, and visible for many miles around. The town was used in the film Tea with Mussolini, and is the setting for the video game Assassin’s Creed II !

For their final concert the choir perform in one of Florence’s most ancient churches, La Badia Fiorentina (Florence Abbey), which dates back to the year 978, and where Robin is currently organist. The monastic community there have given the choir special permission to give a rare concert, which will be the final highlight of the trip.

The choir also performed this summer programme on two occasions in England. First on Thursday 16th June when the choir sang in the City of London at St Margaret Patten’s Church and then on the opening night of the Sevenoaks Festival at St Martin’s Church Brasted on the 18th June.

Programme

Hugo Kelly – Magnificat

J. Arcadelt – Ave maria

G. Gabrieli – Jubilate Deo a 8

T. Weelkes – When David heard

A. Lotti – Crucifixus a 8

A. Bruckner – Ave Maria, Locus iste, Os justi

C. Wood – Great Lord of Lords

S. Rachmaninov – Blessed is the man

A. Bax – Lord, thou hast told us

E. Bairstow – I sat down under his shadow

J. Rheinberger – Double mass in E flat

W. Harris – Bring us, O Lord God

Programme notes

Music is the harmonious voice of creation; an echo of the invisible world. Giuseppe Mazzini

In March 1861, Victor Emmanuel II became the first King of a unified Italy thanks largely to the work of politicians Mazzini and Cavour and the revolutionary leader Giuseppe Garibaldi. Since the fall of the Roman Empire, Italy had developed as a number of city states and small republics such as Venice, Florence, Siena and Naples. The Pope governed the Papal States but there was constant political upheaval and insurgence as the Holy Roman Emperors in the north vied with the Popes for power.

Despite, or perhaps because of, the constant power struggles, Italy was the centre of the world for both trade and the arts. Florence, especially under the Medicis, was a forcing ground for art and architecture. Venice was at one time the most powerful trading state in the world and its art and music flourished alongside. Musicians learned their craft in Italy and the instrument makers provided their tools. Song was everywhere.

The first half of our programme consists of music, which was either written during this time of renaissance and cultural domination or was inspired by precepts of vocal purity and faithfulness to the liturgical text, associated with sacred Italian music. By 1861, the Italians were really only interested in opera and so we turn to composers from other countries for our second half of astonishing sacred choral works. All lived in times of struggle of empires and revolution. All found inspiration in religious texts and all owe something to the choral traditions first laid down in Renaissance Italy.

Henry Kellyk is the earliest and least known of our composers. An Englishman of the mid-15th century, only two of his works survive. He starts us in the late Medieval world, opening with plainchant, which the monks knew by heart. His music elaborates the words in layers of rhythmically complex melismas, which render the text incomprehensible but the sound would have rung around the lofty churches as ‘the harmonious voice of creation’.

Ave Maria, like the Magnificat, is one of the Marian texts and we have two settings in our programme. The cult of Mary was strong in the Catholic Church but lessened in the protestant liturgies after the Reformation. The version by Jacob Arcadelt demonstrates the dramatic change brought about by the Council of Trent. He was a Flemish composer working in Rome and understood well the Council’s intention to place text at the centre of church music. Music from this time must be simple and dignified.

Giovanni Gabrieli was working in another state, in Venice. Away from the direct gaze of the Pope, music here was a more glittering affair and instruments were commonly added. Voices and instruments were often used together and in opposition. The Jubilate Deo is for eight voices creating a rich tapestry of overlapping lines.

Thomas Weelkes in England spent most of his life under the patronage of Chichester Cathedral. Although a later piece, possibly written at the death of Prince Henry in 1612, the sacred madrigal When David heard that Absolom was slain draws on elements old and new. The 6-part setting is rhythmically straight-forward but the uneasy tonality takes us back to medieval false relations, where one part sharpens notes while another is flattening them. The result is a particularly poignant expression of the grief of a father for his dead son.

The 8-part Crucifixus by Antonio Lotti takes Weelkes’ use of dissonance to a whole new level. The only points of harmonic resolution come in three places, emphasizing ‘crucified’, for ‘us’ and ‘buried’. The strain and agony is intense.

It is for Anton Bruckner to take us forward now to unification and this he does musically as well as temporally. His motets are written in a simple style to ensure that the text is paramount but his harmonic language is romantic. This time, it was not the Council of Trent which gave guidance to sacred composition. The Cecilian Movement established itself across Europe and America to reduce the operatic theatricality in oratorios and other sacred pieces, which had become prevalent.

Across Europe, Christian worship had developed many branches: Roman Catholicism, eastern Orthodoxy, Protestant Methodism, the Anglican communion and so on. Charles Wood was a Cambridge organist and composer steeped in the Anglican traditions. Blessed is the Man by Rachmaninov comes from his Russian Vespers. Edward Bairstow mainly worked in churches in northern England and in York Minster. Arnold Bax was an orchestral composer but this simple gem reminds us that much of the English Hymnal was written by first-rate composers.

Finally, Joseph Rheinberger’s Eb Mass more than nods to the Cecilian belief that plainness is next to godliness. It also harks back to the antiphonal choirs of Renaissance Venice and so brings our concert full circle, ‘an echo of the invisible world’.

Sara Kemsley