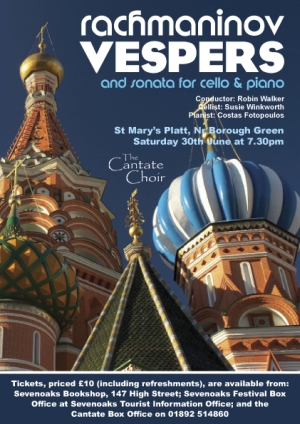

7.30pm, Saturday 30 June 2007 – St Mary’s Platt, Nr Borough Green

Soloists

Susie Winkworth – cello

Costas Fotopoulos – piano

Programme

Sergei Rachmaninov 1873-1943 – All-Night Vigil

Sergei Rachmaninov – Sonata for Cello & Piano in G Minor, Op. 19

Sergei Rachmaninov – Morceaux de Salon, Op. 2

Programme notes

Orthodoxy is first of all the love of beauty. Our entire life must be inspired by the vision of heavenly glory, and this contemplation is the essence of Orthodoxy… Russian asceticism aims at manifesting God’s kingdom on earth. It does not deny this world, but embraces it. (S N Bulgakov)

The Eastern Orthodox Church, which thrives today particularly in Russia, Bulgaria and Greece, is arguably the oldest form of Christianity, stemming as it does from the Greek writings of the early apostles. The Byzantine Rite developed as a result of the shift of the seat of imperialism from Rome to Constantinople by Emperor Constantine in 320AD. Of particular significance were the veneration of Mary as Mother of God, and the adoption of icons as symbols of Christ’s presence on earth in human form. The split with Rome was worsened in the 9th century, when the Roman Pope refused to recognise Photius as Patriarch of Constantinople, and again at the time of the crusades and the sacking of Constantinople in 1204.

Since that time, Western Orthodoxy has evolved into many forms, while the Eastern Orthodoxy has been largely preserved as it was. The services always involve music, always voices, never instruments.

In the late 19th century, there was a renaissance among Russian composers, who turned to setting liturgical texts as part of their search for national identity. Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninov were major contributors but a significant school of Russian Church Music, centred in Moscow, developed. It was for this Moscow Synodal Choir that Rachmaninov wrote his setting of the All Night Vigil Op. 37.

Commonly, but incorrectly, known as The Vespers, this work is in fact a setting of three services for the canonical hours: Vespers, Matins and Prime. Vespers begins at sunset and reflects on the idea of Christ as the Light of the World. Movements 1-6 are from this section, and it ends with Gabriel’s salutation to Mary “Blessed art thou among women”. Matins (movements 7-14) meditates upon ideas of Christ in human form and ultimately the Resurrection, the most significant aspect of all in the Christian faith. This takes us to dawn and to Prime, the first hour of the day. Rachmaninov chooses to set just one text, the final triumphant movement, ‘To Thee, triumphant leader of triumphant hosts’. This is the eternity of Heaven.

Rachmaninov’s Vigil uses authentic znamenny or medieval chants in seven movements. In two, he prefers Greek chants and three are in the ‘Kiev’ style. Where he invented his own, he described them as ‘conscious counterfeits’, so closely did he keep to the traditional style. What he brings to the setting is often termed choral orchestration. This is almost a symphony, such are the demands made of the human voices: profoundly low bass parts, extreme ranges for other voices, huge dynamic and tonal ranges and many combinations of voices, which are frequently divided to form lush textures. Throughout, however, he preserves a simplicity in the harmonic, largely modal, language. There is no polyphony or fugal writing here, simply beautiful lines threading around the stepwise chants, whether for meditative introspection or praise and proclamation.

The choice of music for cello and piano by Rachmaninov as a counterpoise to this great choral masterwork is perfectly judged. The same yearning for a national identity is here in the use of simple folk melodies and brooding minor keys. There is the same breadth of expression in the sweeps of passion, sublime delicacy and exciting, rhythmic gesturing. The Cello Sonata was written shortly after his second piano concerto in 1901 and shares that same immediate appeal for the listener, as does the poignant and reminiscent Vocalise, familiar in many arrangements. The two pieces Op.2 (Prelude and Orientale) were written in 1892, just as he completed his studies at the Moscow Conservatoire. No mere palate-cleansers or padding here, as some programmes might provide. The intimacy and warmth of the cello tone allows us to ‘embrace this world’ between the choral contemplations upon higher things.

Sara Kemsley