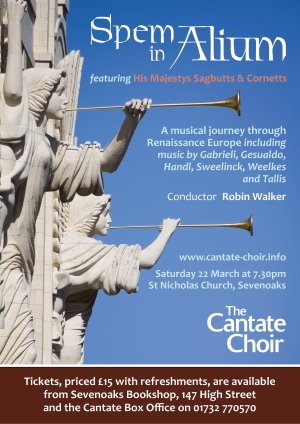

7.30pm, Saturday 22 March 2014 – St Nicholas Church, Sevenoaks

Rejoice in the Lord alway, and again I say rejoice. Philippians 4:4-7

There can be no doubt that much of the greatest western music ever conceived has been done so in affirmation of Christian beliefs and never more so than in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. All over Europe and Britain, composers and performers were learning from each other and competing with each other to pay greater homage to God, to his son Jesus and his mother Mary.

Our musical journey tonight takes us through Italy, into Slovenia and Germany and thence to the Netherlands. From there, we cross the channel to devote the whole of the second half to English pieces and rightly so. The Europeans were good at this time but arguably the English were better. This period under Mary I, Elizabeth I and James I was prosperous but fraught with religious tensions as Catholic and Anglican loyalties were tested beyond the very limits of endurance. Not until the twentieth century does Britain again boast so many composers to equal those of Europe.

Joining us on our journey are the illustrious period instrumentalists, His Majestys Sagbutts and Cornetts. The cornett, put simply, is a wooden trumpet with finger-holes. It is very versatile and capable of great flexibility. This is also true of the narrow-bored sackbut with its slide mechanism. Both could play many more notes than other wind instruments of the time and so were very popular with composers to supplement and complement music for human voices, the pre-eminent medium of the day. Players would often embellish the vocal parts and improvise variations (divisions) in between. Bottrigari in his instrumental treatise of 1594 in Venice said “Cornetts and trombones…play divisions that are neither scrappy, nor so wild and involved that they spoil the underlying melody and the composer’s design: but are introduced at such moments and with such vivacity and charm that they give the music the greatest beauty and spirit.” HMSC have chosen pieces which perfectly complement our programme and also play with us in four pieces after the custom of the day.

Our opening set from Italy demonstrates the extraordinary creative range of the period; Gabrieli effervesces, Palestrina is more thoughtful and considered, Gesualdo you will recall from our last concert is pretty weird for the times but wait until you hear the highly chromatic instrumental piece by Guami!

Moving then to central and northern Europe, you will probably notice a heavier tread and thicker accent, if I may risk such stereotyping! Jacob Handl from Slovenia was a counter-reformation Catholic and therefore the words he set had to be crystal clear. This setting of the Lord’s Prayer is unusual in juxtaposing a high choir with a low one. The German composers (Hassler, Scheidt, Schütz) were familiar with the work of the Italians but their focus on text is keener and they more often point an important phrase or sentence by using homophonic (chordal) music. The Italians perhaps sought to express the emotion of the text more than the meaning. We finish the half with Laudate Dominum by the Dutch organist and keyboard composer Sweelinck. This piece is the best-known of his vocal pieces and it has recognizably keyboard features, especially in the Amen section. The complications in the vocal parts could more easily be rendered by 5-fingered organists!

In England, the great patrons of the arts were the monarch and the cathedrals, which outlived the abbeys and monasteries abolished by Henry VIII. There was a hunger for music which glorified God and Monarch (though not necessarily in that order!) in a style which was recognisably English, for the split from Rome was still recent and, for many, painful. William Byrd and Thomas Tallis were both esteemed members of the Chapel Royal whose music graced every possible royal occasion. Peter Philips was a devout Catholic who therefore spent most of his adult life abroad where he learned from both the Dutch and the Italian composers. Thomas Weelkes spent most of his career at Chichester Cathedral. His writing harks back at times to the old and in the case of this piece about a father mourning the death of his son the medieval false relations (‘wrong notes’) give added poignancy to the expression of grief.

Matthew Locke is the latest of our composers, heading towards the Baroque style but an important composer in England not least in his appointment as composer for ‘the King’s sackbutts and cornets’, the king by now being Charles I. And so we reach the jewel in the crown, Spem in Alium in 40 parts by Thomas Tallis.

It is not known exactly when and why Tallis wrote this piece for eight 5-part choirs mixing voices and instruments at will. The various theories are, however, interesting and give more insights into composing and performing practices of the period. There have been other similarly massive pieces and almost certainly Tallis heard the 40-part motet by Alessandro Striggio when he visited London in 1567. He may well have liked the challenge of doing something similar and better. It could have been written for the 40th birthday of the monarch, Mary in 1556 or Elizabeth in 1573.

Forty is also a symbolic number. It is mentioned 146 times in Scripture and points to or symbolises trial and testing, or probation. Five (voices) and eight (choirs) point to ‘actions through grace’ leading to ‘renewal and redemption’.

Musicologist Denis Stevens believes it was first performed at the Duke of Norfolk’s London home in 1570 or 1571. Norfolk had catholic leanings and the text chosen by Tallis, also still a member of the Catholic Church, makes a point about sin, redemption and humility. This could have been covertly aimed at the queen who was involved in the suppression of Catholics at the time.

Wherefore ever it came into being, this is no hubristic intellectual exercise but a masterclass in controlled polyphony and well-judged homophony. The eight choirs perform separately, in groups and together, and the sheer power of the massive texture is exhilarating. This is how we English, in quires and places where they sing, ‘rejoice in the Lord alway’.

Sara Kemsley