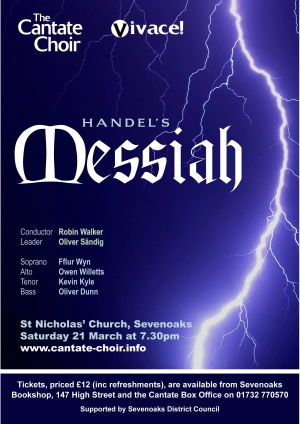

7.30pm, Saturday 21 March 2009 – St Nicholas’ Church, Sevenoaks

Soloists

Fflur Wyn – soprano

Owen Willetts – alto

Kevin Kyle – tenor

Oliver Dunn – bass

Oliver Sandig – leader

Review

Steve Coles – review

Programme

Handel – Messiah

Programme notes

7.30pm, Saturday 21 March 2009 – St Nicholas’ Church, Sevenoaks

Soloists

Fflur Wyn – soprano

Owen Willetts – alto

Kevin Kyle – tenor

Oliver Dunn – bass

Oliver Sandig – leader

Review

Steve Coles – review

Programme

Handel – Messiah

Programme notes

Fflur sang with the choir during its Handel’s Messiah concert in March 2009.

Fflur Wyn graduated with a Dip.RAM from the Royal Academy of Music Opera Course where she studied with Beatrice Unsworth and Clara Taylor. Her awards include First Prize and Audience Prize at the National Handel Competition 2005, the London Welsh Young Singer of the Year 2005, the Kathleen Ferrier Bursary, the Bryn Terfel Scholarship and the MOCSA Young Welsh Singer Prize.

Her operatic performances include Pamina (The Magic Flute – Holland Park Opera); Clerida (Croesus by Keiser), Gretel (Hansel and Gretel) Papagena (The Magic Flute) all for Opera North; Iphis (Jephtha – Welsh National Opera); Karolka (Jenufa – St Endellion Festival with Richard Hickox); Susanna (The Marriage of Figaro – Court Opera); creating the role of Adele in Michael Berkley’s opera Jane Eyre with Music Theatre Wales, with appearances at The Linbury Theatre Covent Garden (BBC Radio 3 / CD Recording).

Her oratorio and concert appearances include Handel’s Messiah (Harry Bicket/English Concert), Bach Christmas Oratorio (Jan Willem de Vriend/Combattimento Consort), Haydn’s Creation (Paul McCreesh/The Gabrieli Consort), her Proms debut in Mozart’s Thamos at Cadogan Hall for the Proms Saturday Matinee series, Handel’s Jephtha (Daniel Reuss/Cappella Amsterdam), Mozart Exsultate Jubilate with both the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and The European Union Chamber Orchestra, Mozart Mass in C minor (Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra), Bach St John Passion (David Hill/Opera North Orchestra).

Future performances include Barbarina in Le Nozze di Figaro at La Monnaie.

Reviewer – Steve Coles

More often than not in my experience, performances of Messiah catch the unwary out. There are just too many hidden obstacles to surmount and standards these days of period performance concerts seem to get higher and higher. Choice of soloists, that is those singers who are Handelian, choice of cuts and probably most important, and choice of speeds, (for there is nothing worse than a dragging Messiah with endless pause to boot between the items), are three such considerations. Then again one must remember that here is a work that needs much more concert day rehearsal time than time or finances permit.

What strikes me, however, is that on every occasion one hears Messiah, something new comes through, whether it is a certain musical phrase one hears differently or a particular tingle factor moment from a soloist or player and one is never disappointed as one is drawn by the music into that special world when the music makes time stand still.

Having put all these obstacles in the way, The Cantate Choir presented Messiah with four young soloists who gave more than creditable performances and a lively band Vivace! formed to work with them and conductor, Robin Walker, and it was The Cantate Choir who were the stars of the show. Their remarkable attention to detail and nuance must surely rate them as one of the top chamber choirs in the South East, if not farther afield. What they lack in professional timbre, (which for me is often itself a negative point), in fact gives them a quality which remains refreshing from beginning to end.

I must confess a personal interest as provider of the keyboard instruments for the gig but would like to mention Robin Walker’s intuitive harpsichord continuo playing, assisted by the German organist, Martin Knizia, who persuaded me to offer Werkmeister III as the unequal temperament which sat well especially in the more distant keys that Handel uses. The strings and oboes ably sustained their formidable unison passage throughout the work which in itself is far far harder than might seem. Rob Farley’s trumpet always enthrals. I know it is a hard work to play but I really miss the B section, arguably the best few bars of the whole work, and then the potential firework opportunities of the recapitulation, but then something also would have to go!

Singing is probably the most subjective art form there is but for my own taste I found Fflur Wyn and Kevin Kyle’s renderings occasionally rather un-Handelian, surprisingly so as they were both finalists at the London Handel Competition, indeed Miss Winn, who has a most striking voice, was a former winner. The alto Owen Willetts certainly had the most formidable power but seemed to lack the transparent quality that the music so often suggests, whilst the bass, Oliver Dunn, passed the finishing line with flying colours; he was certainly able to cope with the range of the two big contrasting arias that Handel demands.

A capacity audience was not disappointed and it was a pleasure to witness a performance, directed as Handel would have done, from the harpsichord by Robin Walker, who with his team and especially his choir, should be proud of taking us all so ably to that place where time, for a moment, stood still and allowed us to reflect on one of the seven wonders of musical history.

Steve Coles

Artistic Director

Tudeley Festival

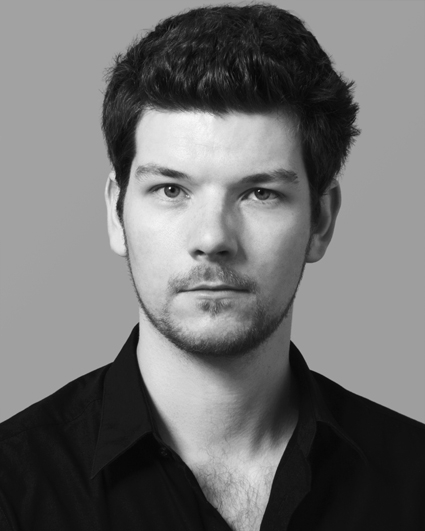

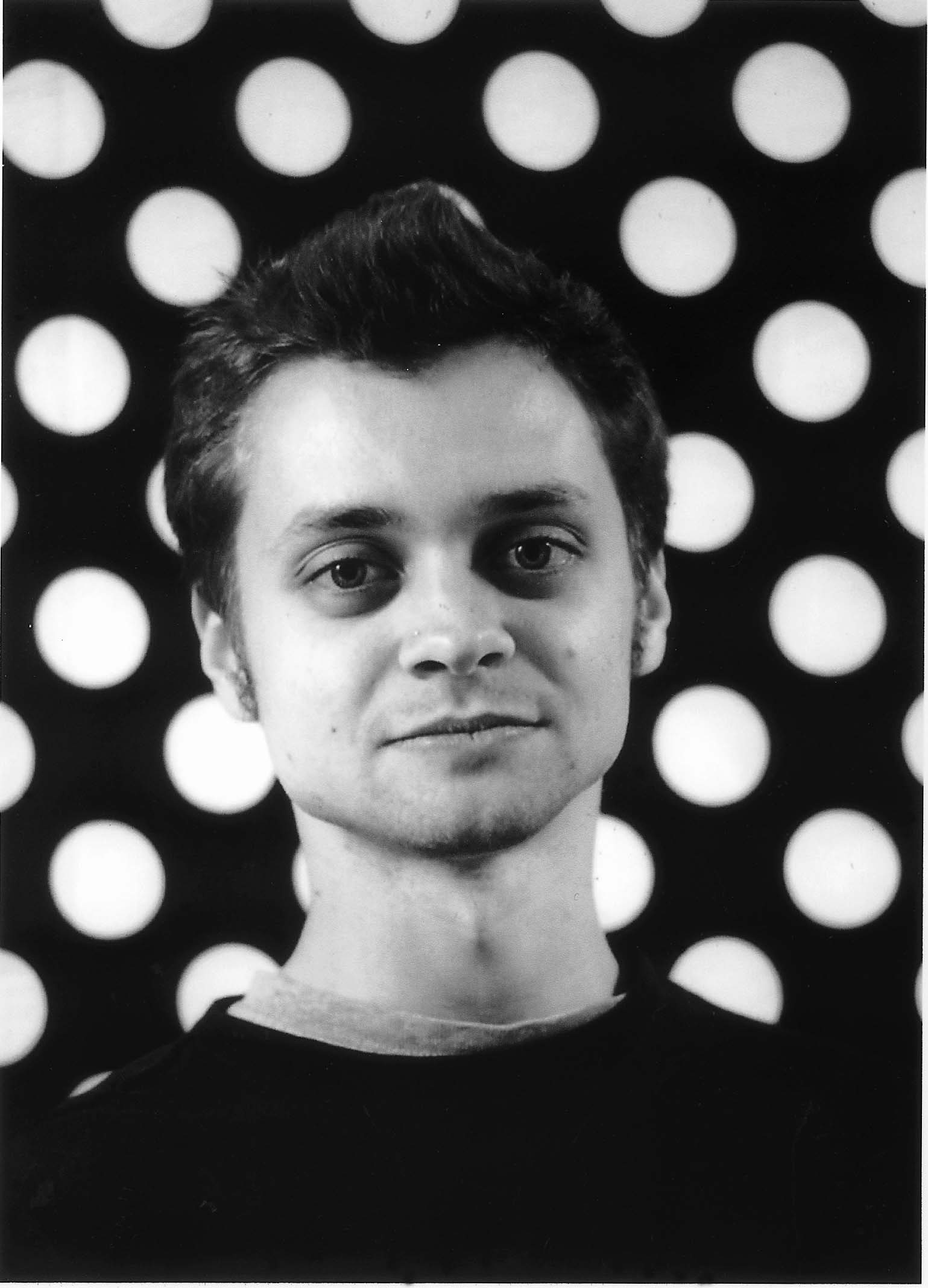

Oliver sang with the choir during its Handel’s Messiah concert in March 2009.

Man of Kent, Oliver Dunn is currently studying on the Opera Course at the Royal Academy of Music, where he studies with Mark Wildman and Iain Ledingham. Previously to this he completed a degree and two Post Graduate years of study at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester under the tutelage of Robert Alderson.

On the concert platform he has appeared extensively across Britain with a variety of orchestras and ensembles including, The Hallé, The Hanover Band and Manchester Camerata. Oratorio performances include Mozart’s Vesperae Solennes de Confessore, Bach St Matthew Passion and St John Passion (Christus), Mendelssohn Elijah, Handel Messiah, Haydn Nelson Mass, Rossini Petite Messe Solennelle, Puccini Messa di Gloria, Purcell King Arthur and Karl Jenkins’ The Armed Man, conducted by the composer. Oliver also performed concert excerpts of Disney’s The Jungle Book and The Lion King with the RNCM Wind Orchestra at the Bridgewater Hall in which he played the roles of Baloo and Scar.

Since his arrival at the Royal Academy Oliver has taken part in masterclasses with Chevalier José Cura, Dennis O’Neill and Robert Tear, as well as performing excerpts of Cosi fan Tutte and Rossini’s Il viaggio a Reims in the ‘5 days, 100 Concerts’ opening festival of the new King’s Place Concert venue close to King’s Cross Station.

7.30pm, Saturday 21 March 2009 – St Nicholas’ Church, Sevenoaks

Soloists

Fflur Wyn – soprano

Owen Willetts – alto

Kevin Kyle – tenor

Oliver Dunn – bass

Oliver Sandig – leader

Review

Steve Coles – review

Programme

Handel – Messiah

Programme notes

2009 is the 250th anniversary of Handel’s death, and what better way to celebrate the work of England’s most famous and enduring composers than to hear Messiah, the dramatic musical drama of Jesus’ life.

Handel famously composed Messiah in only a few hectic days, creating a work which has been performed every year since it’s first performance, a unique achievement. It is no surprise the work has found such fame, containing as it does so many memorable pieces, including possibly the most famous and recognisable of any, the Hallelujah chorus. Messiah is really Opera for the church, and the drama of the narrative carries us through chorus, aria and recitative for a thoroughly engaging and entertaining evening.

In a small London house on Brook Street, a servant sighs with resignation as he arranges a tray full of food he assumes will not be eaten. For more than a week, he has faithfully continued to wait on his employer, an eccentric composer, who spends hour after hour isolated in his room.

Morning, noon, and evening the servant delivers appealing meals to the composer and returns later to find the bowls and platters largely untouched.

Once again, he steels himself to go through the same routine, muttering under his breath about how oddly temperamental musicians can be. As he swings open the door to the composer’s room, the servant stops in his tracks.

The startled composer, tears streaming down his face, turns to his servant and cries out, “I did think I did see all Heaven before me, and the great God Himself.” George Frederic Handel had just finished writing a movement that would take its place in history as the Hallelujah Chorus.

(from Spiritual Lives of the Great Composers by Patrick Kavanaugh)

George Frederic Handel was born in Saxony in Germany in 1685 but from 1712 he resided almost solely in England, patronised by Kings George I and II so that he has rather been adopted as an English composer (and, heaven knows, we have few enough great composers as of right!) He had enjoyed enormous critical and financial success as a composer of operas but by 1741 his fortunes had fallen mightily. His operas were regarded by many as scurrilous and the Covent Garden Theatre, which he ran, a ‘den of rascals’. He was close to ruin and the debtors’ prison.

Out of the blue, two letters arrived, which changed Handel’s position and musical history forever. First came an invitation from the Duke of Devonshire to come to Dublin and provide a series of benefit concerts ‘For the relief of the prisoners in the several gaols, and for the support of Mercer’s Hospital in Stephen Street, and of the Charitable Infirmary on the Inn’s Quay’. Then, a letter arrived from Charles Jennens, a literary scholar and editor of Shakespeare’s plays, who had previously written libretti for Handel. The letter contained Old and New Testament texts, which Handel read and re-read and was so moved that he immediately embarked on writing a sacred opera using them. Messiah premiered on April 13, 1742 in Dublin as a charitable benefit, raising £400 and freeing 142 men from debtor’s prison. It has not been out of performance for a single year since, a record unsurpassed by any other classical work.

Handel believed that God spoke to him and required him to write the piece down. It was performed again and again for charitable concerts and Handel would not take a penny from the ticket sales, believing that God, not he, had written the piece. At his death, he bequeathed the manuscript and parts to the Foundling Hospital, founded by Thomas Coram in 1739, which continues to benefit to this day from performances of the Messiah. Charles Burney, 18th century music historian, remarked that Handel’s Messiah “fed the hungry, clothed the naked, and fostered the orphan.”

Why then, is Messiah such an enduring and monumental piece? Why is it performed every year all over the world? Why are there choral societies committed to performing nothing else?

For one thing, it is a work whose three parts take in the entire sweep of the traditions and beliefs of the Christian faith:

Part One — Prophecy of Salvation, the birth of Christ Jesus

Part Two — Crucifixion and Death

Part Three — Resurrection and the promise of eternal life for believers

A complete performance requires nearly three hours and therefore it is common to hear cut versions, particularly those around Christmas time, which focus on Part I with other good bits thrown in.

The second reason for its recurrent popularity is that it is simply full of good tunes and rousing choruses, which enable us as Everyman to grasp something of the ineffable mysteries of these sacred texts and to go away feeling spiritually uplifted regardless of our beliefs and understandings.

The main reason, however, has to be the sheer genius of the man (or perhaps it really was his divine inspiration). Handel paints the texts so vividly and gloriously that it seems impossible not to be profoundly moved by each and every aria, chorus and instrumental interlude. The contents page reads like a Classic FM 50 greatest hits countdown and this is no accident. Each and every piece is immaculately conceived in melodic, harmonic and textural terms and thus is as unforgettable as Michaelangelo’s David or Da Vinci’s Last Supper. But theirs were single pieces and this is a mighty collection of such works.

To begin the countdown, who can forget the affirmative ‘And the Glory, the Glory of the Lord’ as it strides upwards in A major to its home note? Or, after the ferocious portent of his coming ‘as a refiner’s fire’, the chorus delicately sprinkling water upon us in ‘And he shall purify’? Next, ‘For unto us a child is born’ uses the melody of a love song previously used in one of Handel’s operas and is simply the joyous babble of the christening party. In Part II, can there be a more gut-wrenching portrayal of misery and betrayal than the aria ‘He was despised and rejected of men’? It relentlessly pursues the falling semitone, long acknowledged to be as close to a human sigh as mere notes can be.

We all know the Hallelujah Chorus and it is traditional to stand for it as King George II spontaneously did when he first heard it. But it is the words which begin Part III, ‘I know that my Redeemer liveth’, which were inscribed on Handel’s tomb in Poets’ Corner, Westminster Abbey when he died in 1759. Written in the optimistic, bright and certain key of E major, the opening two notes (dominant rising to tonic) sum up for me the entire piece; without any shadow of a doubt, with no possibility for confusion, Handel says, ‘I believe’.

Sara Kemsley

Oliver led the orchestra for the choir’s Handel’s Messiah concert in March 2009.

Oliver Sandig studied in Trossingen and the Royal College of Music. It was through the European Union Baroque Orchestra that he started his career in Early Music. He regularly plays with Florilegium, The Sweelinck Ensemble, Vivace and with Charivari Agréable with whom he recorded Torelli’s Brandenburg Concertos in 2008. He is a regular player with Café Mozart and with them recorded a CD of the music of the Earl of Abingdon and works.

Oliver also pursues a career in making and tuning harpsichords.

Owen sang with the choir during its Handel’s Messiah concert in March 2009.

Owen began singing as a choral scholar at Lichfield Cathedral. He then went on study at the Royal Academy of Music, where he spent four years studying with Noelle Barker, Iain Leadingham and David Lowe.

Owen has worked on the concert stage with many of the leading names in historical performance, including John Elliot Gardiner, Emmanuelle Haim, Laurence Cummings, Richard Egar and Christian Curnyn. With the Irish Baroque Orchestra Owen has performed Vivaldi and Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater and Bach’s St. John Passion.

In opera, Owen has performed the role of Ottone in Monteverdi’s L’Incoronazione di Poppea with Laurence Cummings and the Royal Academy Opera and for the Rekjavik Summer Opera; Anfinomus and Humano Fragilitata for Graham Vick and the Birmingham Opera Company, and covered the role of Pastore Uno for Emmanulle Haim in Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo. Owen performed the role of Satirino in Cavalli’s La Calisto, for the Iford Festival, with Christian Curnyn and the Early Opera Company. Owen covered the role of The Innocent in Harrison Birtwistle’s new opera The Minotaur, at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, and again at the ROH, the role of Satirino in Cavalli’s La Calisto. For the Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Owen covered the role of Ottone in Monteverdi’s L’Incoronzione di Poppea. Again with Emmanuelle Haim, he performed Purcell’s The Fairy Queen, which toured France, Belgium and the Netherlands. This Summer Owen will cover the role of Tolomeo in Handel’s Giulio Cesare for the Glyndebourne Festival Opera, and will sing the role of Ottone in Monteverdi’s L’Incoronazione de Poppea for Christian Curnyn and the Early Opera Company.